# Explore the shocking and surprising history behind the development of Resident Evil. From scrapped games to happy accidents, uncover 10 Development Secrets Behind the Resident Evil Saga…

Geminvo – The creak of a door, the chilling moan from down a dark hallway, the desperate count of your last few bullets. For millions, these are the sounds that defined a genre. When Resident Evil first shambled onto the PlayStation in 1996, it did more than just scare players; it created a new language for fear in video games. But the story of how this legendary franchise came to be is just as tense, unpredictable, and full of shocking twists as any trip through the Spencer Mansion. The development of Resident Evil was not a clean, straightforward process. It was a chaotic journey of happy accidents, painful sacrifices, and underdog triumphs.

This deep dive, compiled from developer interviews, historical archives, and official artbooks, pulls back the curtain on ten of the most incredible stories from behind the scenes. You’ll discover the forgotten games that served as its blueprint, the legendary sequels that were scrapped at the last minute, and the bizarre B-movie charm that was born from a perfect storm of low budgets and linguistic mishaps. This is the untold Resident Evil history—a tale as thrilling as the games themselves.

Read More : The Definitive Guide to PS1 Survival Horror Games, From Resident Evil to Silent Hill…

1. The Haunted Blueprint: It All Started with ‘Sweet Home’

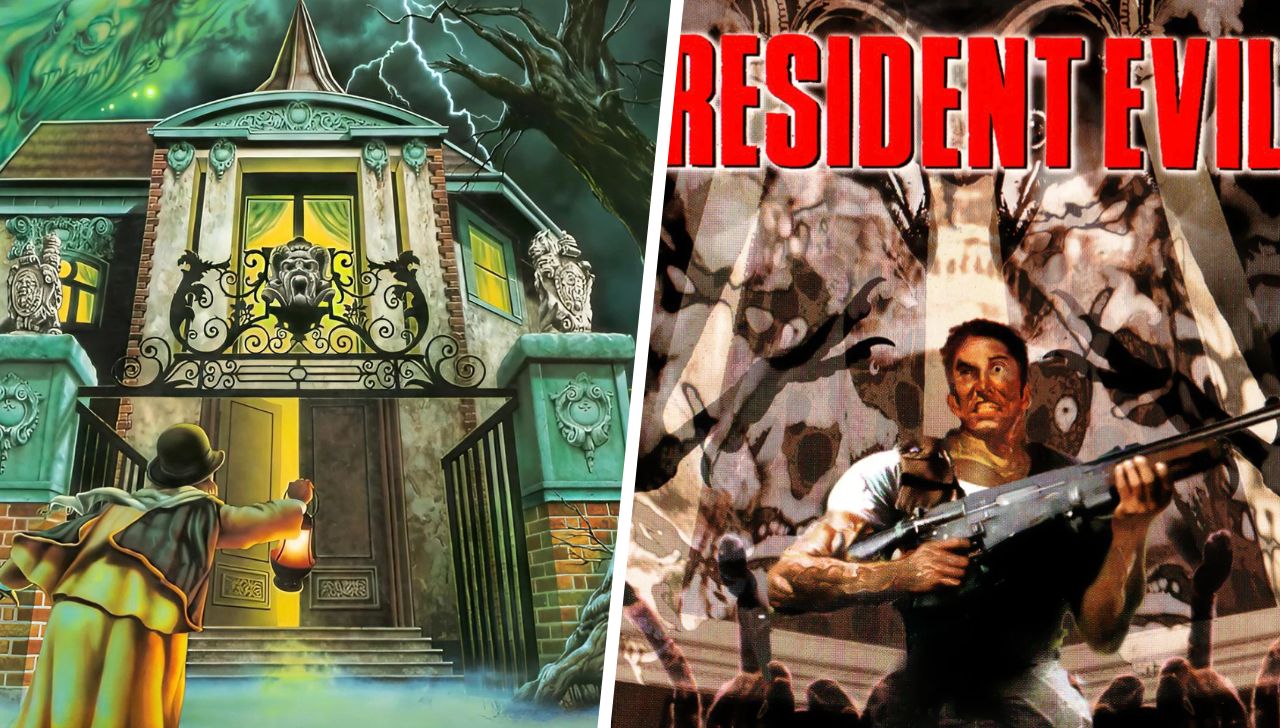

Long before the world knew the name Spencer Mansion, there was the Mamiya House. The entire concept for Resident Evil began in 1993 when producer Tokuro Fujiwara tasked a young director named Shinji Mikami with a deceptively simple goal: remake Fujiwara’s 1989 Famicom horror RPG, Sweet Home.

Sweet Home, based on a Japanese horror film of the same name, was a cult classic in Japan but never saw a Western release. It was a game ahead of its time, forcing players to navigate a terrifying mansion with limited inventory space, solve environmental puzzles, and uncover a dark story through scattered notes—a formula that sounds remarkably familiar.

The influence of Sweet Home on Resident Evil is undeniable and profound. The Spencer Mansion is a direct spiritual and aesthetic successor to the Mamiya House, sharing its eerie, European-style decor and using foreboding artwork to advance the narrative. Core gameplay mechanics that would define the survival horror origin were lifted directly from the 8-bit title, including the tense inventory management, the use of diary entries for storytelling, and even the iconic door-opening animations, which were a clever way to mask loading times. One of Resident Evil’s most famous jump scares, the “Turning Around Zombie,” is a direct homage to a similar enemy encounter in Sweet Home.

However, a crucial twist in the development process turned this remake into a revolution. Capcom no longer held the rights to the Sweet Home property, forcing the team to create an entirely new universe. This limitation proved to be a blessing in disguise. Instead of being tied to a Japanese ghost story, Mikami’s team was free to create something new, drawing inspiration from George A. Romero’s zombie films to craft the lore of the Umbrella Corporation and the S.T.A.R.S. team. By taking the mechanical soul of Sweet Home and dressing it in a new, more globally accessible B-movie horror aesthetic, the team didn’t just remake a game; they created the definitive template for a new genre.

2. The Game That Never Was: The Legend of ‘Resident Evil 1.5’

The success of the first Resident Evil was a surprise, even to Capcom, and a sequel was immediately greenlit. However, the Resident Evil 2 that fans know and love is not the game the team originally made. In one of the most famous stories of Capcom development, the first version of the sequel, now known to fans as Resident Evil 1.5, was developed to roughly 60-80% completion before being completely scrapped.

This lost game was a radically different experience. The female protagonist was not Claire Redfield but Elza Walker, a blonde college student and motorcycle racer with no connection to the original game’s cast. Leon S. Kennedy was present, but he was a seasoned police veteran, not a rookie on his first day. The Raccoon Police Department was a modern, grounded, and realistic precinct, a far cry from the gothic, museum-like building of the final version. Most importantly, the story was designed to be the end of the series. It began with Umbrella’s crimes already exposed and the corporation on the brink of collapse, intending to wrap up all loose ends.

So why throw it all away? According to Shinji Mikami, the game simply “was no fun”. The team, including first-time director Hideki Kamiya, felt the project lacked a clear direction and the setting was visually uninteresting compared to the Spencer Mansion. But beyond creative dissatisfaction, a strategic reality had emerged. The first game wasn’t just a hit; it was a phenomenon. A sequel that ended the story was now a commercial dead end. The franchise needed to expand, not conclude. The decision to scrap Resident Evil 1.5 was a painful but necessary sacrifice.

By starting over, the team could create a more cinematic and engaging game while also re-engineering the narrative for longevity. The replacement of Elza Walker with Chris’s sister, Claire Redfield, was the crucial first step in building an interconnected universe of characters, ensuring the series had a future far beyond Raccoon City. As a nod to this fascinating chapter of Resident Evil history, Elza’s biker outfit was included as an unlockable costume for Claire in the Resident Evil 2 Remake.

Read More : Capcom’s Lost World: The Definitive Case for a Dino Crisis Remake

3. A Genre is Born: How Capcom Coined “Survival Horror“

Today, “survival horror” is a cornerstone of the video game lexicon, but in 1996, it didn’t exist. The term was invented by Capcom’s marketing department specifically to promote the Japanese release of Biohazard. While games with horror elements had existed for years—from the Atari 2600’s Haunted House (1982) to the influential Alone in the Dark (1992)—they lacked a unifying genre name, often being filed under “action-adventure”.

The marketing team faced a unique challenge: how do you sell a game that intentionally makes the player feel weak and vulnerable? The gameplay was slow, the controls were clunky, and resources were incredibly scarce. It was the antithesis of the power fantasies that dominated the market. Their solution was a stroke of genius. The term “survival horror” perfectly encapsulated the game’s core loop. “Survival” communicated the desperate struggle for resources—managing a limited inventory of ammo, health items, and even typewriter ribbons to save your game. “Horror” set the atmospheric tone, promising a terrifying experience.

This act of naming was a form of creative canonization. It provided a lens through which players could understand and appreciate the game’s unconventional design. The clunky “tank controls” and fixed camera angles weren’t bad design; they were tools to heighten tension and make you feel helpless. The limited ammo wasn’t a flaw; it was a core part of the survival challenge.

The term was so effective that it not only defined Resident Evil but also retroactively defined its predecessors and created a clear blueprint for all the games that would follow in its wake, from Silent Hill to Dead Space. It was a rare and powerful moment where a marketing buzzword became an essential and permanent part of gaming culture.

4. “Jill Sandwich” & Cheesy Intros: The Story Behind RE1’s B-Movie Charm

“You were almost a Jill sandwich!” It’s a line so famously bad that it has been immortalized in gaming history. The original Resident Evil is legendary for its B-movie charm, from its laughably terrible live-action intro to its stilted English voice acting. This wasn’t entirely an accident; the team was actively trying to emulate the feel of low-budget American horror films. However, the way they achieved this was a perfect storm of budgetary constraints, cultural misinterpretations, and flawed production processes.

The infamous live-action intro was filmed on a shoestring budget near Tokyo, featuring a cast of mostly foreign exchange students and local actors who were not professional thespians. The actors received very little direction from the commercial filmmaker hired for the shoot, leading to awkward, unconvincing performances. The original cut was far gorier and filmed in color, but it was censored and converted to black-and-white for the Western release, adding to its schlocky feel.

The voice acting suffered from a similar, bizarre process. Surprisingly, the game was released with only an English voice track, even in Japan, after an initial Japanese recording was deemed too poor. The English-speaking actors were handed their lines on an Excel spreadsheet with absolutely no context for the scenes. They would record multiple takes with different inflections, and then the Japanese sound engineers—who were not native English speakers—would choose the take they thought had the best “rhythm” or sounded the “coolest”.

This resulted in dialogue with bizarre emphasis and nonsensical tones, culminating in the game winning a Guinness World Record for “Worst Game Dialogue”. The result of this chaotic production was a kind of accidental authenticity. A polished, high-budget production would have felt like a sterile imitation of a B-movie. Instead, the “jank” of the final product perfectly captured the exact atmosphere the developers were aiming for, making the game far more memorable and endearing than if it had been competently but forgettably produced.

5. A Devil’s Bargain: The Scrapped RE4 That Became ‘Devil May Cry‘

The road to Resident Evil 4 was long, tortuous, and littered with the corpses of discarded prototypes. The game went through at least four scrapped versions before it became the over-the-shoulder masterpiece that revolutionized the industry. The very first of these failed attempts, however, was so promising that it refused to stay dead. This version was helmed by Hideki Kamiya, the director of Resident Evil 2, who envisioned a radical departure for the series.

Kamiya’s concept was a “cool” and “stylish” action game, a world away from the slow, methodical horror of the previous titles. The story focused on a new protagonist named Tony, an invincible man with superhuman abilities granted by biotechnology, and featured a dynamic camera system instead of the traditional pre-rendered backgrounds. While the concept was exciting, series creator Shinji Mikami ultimately felt it strayed too far from the core identity of Resident Evil.

A lesser producer might have simply cancelled the project and salvaged what they could. Mikami, however, saw the potential in Kamiya’s vision, even if it wasn’t right for his franchise. In a masterstroke of creative management, he encouraged the team to remove the Resident Evil elements and develop the concept as a brand-new, original IP. That project was spun off and became Devil May Cry (2001), a title that launched another one of Capcom’s most successful and beloved franchises. This moment of creative conflict became an engine for diversification.

It allowed Resident Evil 4 the time it needed to eventually find its own identity, while simultaneously birthing a completely different blockbuster series from the ashes of a “failed” prototype. It stands as a powerful testament to how a single development dead-end can lead to a doubling of creative and commercial success.

6. The Underdog Project: Capcom’s B-Team Masterpiece

In the mid-90s, Capcom was a titan of the arcade scene, and its internal hierarchy reflected that. The company’s top talent and resources were funneled into its flagship fighting game series, Street Fighter. In this environment, the project that would become Resident Evil was seen as a low-priority, experimental title. The development team was largely composed of young, inexperienced creators, many of whom were working on their very first game. For some, being assigned to the project was even viewed as a “kind of demotion”.

This lack of internal faith was palpable. Shinji Mikami recalled working on the game by himself for the first six months before Capcom granted him a small team. The team struggled with the new PlayStation hardware, suffering from a shortage of development tools and clashing over creative decisions in a process of constant “trial and error”. The higher-ups at Capcom seemed to have little confidence that this strange, slow-paced horror game would find an audience.

However, this underdog status became the project’s secret weapon. While the Street Fighter team operated under the immense pressure of corporate oversight and fan expectations, the Resident Evil team was largely left to its own devices. This lack of scrutiny fostered an environment of creative freedom. Unburdened by the weight of expectations, the novice team was able to experiment and take risks that a more conservative, veteran team might have avoided.

The slow pace, the punishing resource scarcity, the B-movie aesthetic—these were all unconventional choices that could have been smoothed out in a more high-profile development cycle. It was precisely because no one was paying close attention that the team was able to create something so radically new, a masterpiece that would ultimately define a genre and become one of Capcom’s most important properties.

7. What’s in a Name? From ‘Biohazard’ to ‘Resident Evil’

In Japan, the series has always been known by its original title: Biohazard (バイオハザード, Baiohazādo). It’s a direct, clinical name that perfectly suits the game’s story of a viral outbreak. However, when Capcom’s American division began preparing the game for its 1996 Western release, they hit a legal snag. They discovered that the name “Biohazard” was already in use by both an MS-DOS game and a metal band from New York, making it impossible to trademark.

Forced to find a new title, Capcom USA held an internal contest among its staff. The winning entry was “Resident Evil,” a clever pun that referenced the game’s primary setting (a residence) and its malevolent inhabitants. While the name has since become iconic, it was not universally loved at the time. Series creator Shinji Mikami has publicly stated his dislike for the Western name, calling it “nonsense” and preferring the original Biohazard.

This forced name change, born from a legal hurdle, had an unintended and arguably positive effect on the franchise’s brand identity in the West. While “Biohazard” evokes sci-fi and action, “Resident Evil” has a more gothic, atmospheric quality. It speaks to classic horror tropes of haunted houses and lurking, unseen evil, which was a much better fit for the slow-burn, claustrophobic terror of the first game. This accidental rebranding helped shape the Western perception of the series, leaning more heavily into its horror elements and creating a name that is now synonymous with the genre it helped create.

8. Lost in Development: First-Person Views, Co-op, and a Comedic Hero

The final version of the original Resident Evil feels like a singular, focused vision, but its development was a crucible of ambitious and sometimes wild ideas that were ultimately left on the cutting room floor. These scrapped concepts offer a fascinating glimpse into what the game could have been and, in many ways, what the franchise would eventually become.

One of the earliest concepts for the game was a first-person shooter, in the vein of the then-massively-popular DOOM. Mikami was intrigued by the immersive potential of this perspective, but the original PlayStation‘s hardware struggled to bring his vision to life, and the idea was abandoned in favor of the third-person, fixed-camera view. Another incredibly ambitious feature planned was two-player co-op. Early beta footage from 1995 clearly shows both Chris Redfield and Jill Valentine exploring the Spencer Mansion together. This feature was also cut due to technical limitations, and true co-op wouldn’t appear in the mainline series for nearly a decade.

The cast of characters was also different in early stages. In addition to Chris and Jill, the team planned a third playable character named Dewey, a Black supporting character described by Mikami as a wisecracking, “Eddie Murphy-type” who was cut about six months into development. These lost ideas are more than just trivia; they are the ghosts of the franchise’s future. The first-person perspective, too ambitious for 1996, would lay dormant for two decades before being resurrected as the core of the series’ terrifying and successful reboot,

Resident Evil 7: Biohazard. The dream of co-op would eventually be realized in spin-offs like Outbreak and become a central feature of later, more action-oriented titles like Resident Evil 5. The cutting room floor of the first game was, in essence, a preview of the series’ long and varied evolution.

9. A Kind of Magic: The Unlikely Queen Connection

Among the many strange and wonderful Resident Evil facts, one of the most charming is the series’ recurring, and seemingly random, tribute to the legendary British rock band Queen. This running gag, which spans multiple games, is a clear indicator that at least one influential developer at Capcom is a massive fan.

The trail of Easter eggs begins in the very first game. On Chris Redfield’s unlockable alternate costume, the phrase “Made in Heaven” is emblazoned on the back—the title of Queen’s final studio album, released in 1995. The reference continues in Resident Evil 2, where Chris’s sister, Claire, wears a jacket with the exact same “Made in Heaven” design.

By the time of Resident Evil: Code Veronica, Claire has a new jacket, but the tribute remains; it now reads “Let Me Live,” the name of a track from the Made in Heaven album. The connection doesn’t stop with the Redfield siblings. In the prequel, Resident Evil 0, the character Billy Coen sports a large, intricate tattoo on his arm. Upon close inspection, the design spells out “Mother Love,” yet another song from that same Queen album.

These references serve no gameplay or narrative function. They are purely personal, passionate additions from a creator. Yet, for the community of fans who delight in discovering them, they have become a beloved piece of franchise lore. They add a layer of personality to the world and its characters, suggesting a shared history and taste between the Redfield siblings. It’s a perfect example of how the personal passions of individual developers, even in the smallest of details, can enrich a game’s world and forge a deeper, more intimate connection with its audience.

10. The Romero Legacy: A Zombie Godfather’s Influence and Involvement

It is impossible to discuss the development of Resident Evil without acknowledging the towering influence of one man: George A. Romero. The director of Night of the Living Dead is widely considered the father of the modern zombie, and his films provided the direct inspiration for Resident Evil’s B-movie aesthetic and its slow, shambling undead. The connection, however, goes far beyond mere inspiration.

Recognizing the clear homage, Capcom hired Romero himself to direct a live-action television commercial in Japan to promote Resident Evil 2 in 1998. The collaboration was so successful that Romero was soon tapped to write and direct the first feature film adaptation of the game. He produced a script that was, by all accounts, extremely faithful to the source material. It followed the plot of the first game closely, featuring Chris Redfield and Jill Valentine as protagonists and including iconic monsters like the giant snake, Yawn, and the monstrous Plant 42.

According to reports, both Capcom and the production company, Constantin Films, were pleased with the script. However, the head of Constantin ultimately rejected Romero’s vision, opting instead for the script by Paul W.S. Anderson, which took the series in a much more action-heavy direction and created a new protagonist, Alice.

This decision represents a tragic irony at the heart of video game adaptation history. The game series, born as a loving tribute to Romero’s brand of horror, was ultimately adapted into a film franchise that fundamentally rejected that very vision in favor of flashy spectacle. It remains one of the great “what ifs” of video game movies and a stark example of the perennial conflict between creative faithfulness and commercial filmmaking priorities.

The Enduring Legacy of Innovation and Accident

Looking back on the chaotic, unpredictable, and often serendipitous development of Resident Evil, a clear picture emerges. Legendary franchises are not always born from a perfect, linear plan. More often, they are forged in a crucible of happy accidents, painful sacrifices, and unexpected creative turns. The series’ very identity was shaped by forces beyond its creators’ initial control: a lost license for Sweet Home forced originality; a “boring” sequel in Resident Evil 1.5 was scrapped to ensure franchise longevity; a legal hurdle over the name Biohazard created a more evocative Western brand; and a flawed, low-budget localization process accidentally perfected its B-movie charm.

From its origins as an underdog project at Capcom to its evolution through discarded prototypes that spawned other successful series, the Resident Evil history is a story of adaptation in every sense of the word. It shows that sometimes the greatest innovations come not from a clear vision, but from the messy, human process of responding to limitations, embracing mistakes, and having the courage to start over. It is this chaotic, passionate, and profoundly human element that gave the series its soul and cemented its place as a true pillar of video game history.

Summary of 10 Development Secrets Behind the Resident Evil Saga

- Spiritual Successor: Resident Evil began as a remake of Capcom’s 1989 Famicom horror RPG Sweet Home, borrowing its mansion setting, inventory management, and puzzle-solving mechanics.

- The Lost Sequel: Resident Evil 2 was completely rebooted late in development. The original version, known as Resident Evil 1.5, featured a different protagonist named Elza Walker and a story that was meant to conclude the series.

- Genre Naming: Capcom’s marketing team invented the term “survival horror” to describe the game’s unique focus on resource scarcity and vulnerability, effectively creating and naming a new genre.

- B-Movie Charm: The original’s famously bad voice acting and cheesy live-action intro were the result of a low budget, inexperienced actors, and a flawed localization process where non-English speaking engineers picked dialogue takes.

- Birth of Devil May Cry: A scrapped, action-oriented prototype for Resident Evil 4 directed by Hideki Kamiya was spun off into its own successful franchise, Devil May Cry.

- Underdog Project: The first Resident Evil was a low-priority project at Capcom, staffed by a young, novice team. This lack of oversight gave them the creative freedom to innovate.

- Name Change: The series is called Biohazard in Japan. The name was changed to Resident Evil in the West due to a trademark conflict with an existing game and a band.

- Scrapped Features: The original game initially planned for a first-person perspective and two-player co-op, features that were too ambitious for the PlayStation but would eventually appear in later franchise entries.

- Queen Easter Eggs: A series of recurring Easter eggs referencing the band Queen (specifically their album Made in Heaven) appear on the clothing of Chris Redfield, Claire Redfield, and Billy Coen.

- George A. Romero’s Involvement: The legendary zombie film director George A. Romero, a primary inspiration for the game, directed a Japanese TV commercial for RE2 and wrote a faithful movie script that was ultimately rejected.