# Explore our analysis of Parasite Eve’s narrative, a groundbreaking ‘cinematic RPG’ from Squaresoft. We dissect its perfect blend of sci-fi horror, deep RPG mechanics, and the unforgettable story of Aya Brea. Discover why this PS1 classic remains a masterpiece.

Geminvo – The air in Carnegie Hall is thick with anticipation, a warmth that has nothing to do with the festive Christmas Eve decorations adorning its hallowed walls. Snow falls gently over 1997 New York City, a picturesque scene of holiday peace. On stage, the lead actress, Melissa Pearce, begins her “aria of sorrow”. Her voice soars, captivating the audience.

But as her eyes lock with a young NYPD officer in the crowd, Aya Brea, the performance takes a horrific turn. A heat surges through the theater, and in an instant, the audience and cast erupt in a terrifying spectacle of spontaneous human combustion, their bodies melting into a grotesque, slimy orange mass. Only Aya remains unharmed, standing amidst the inferno, her date forgotten, her pistol drawn. This is the opening scene of Parasite Eve, and it is more than just a shocking introduction; it is a declaration of intent.

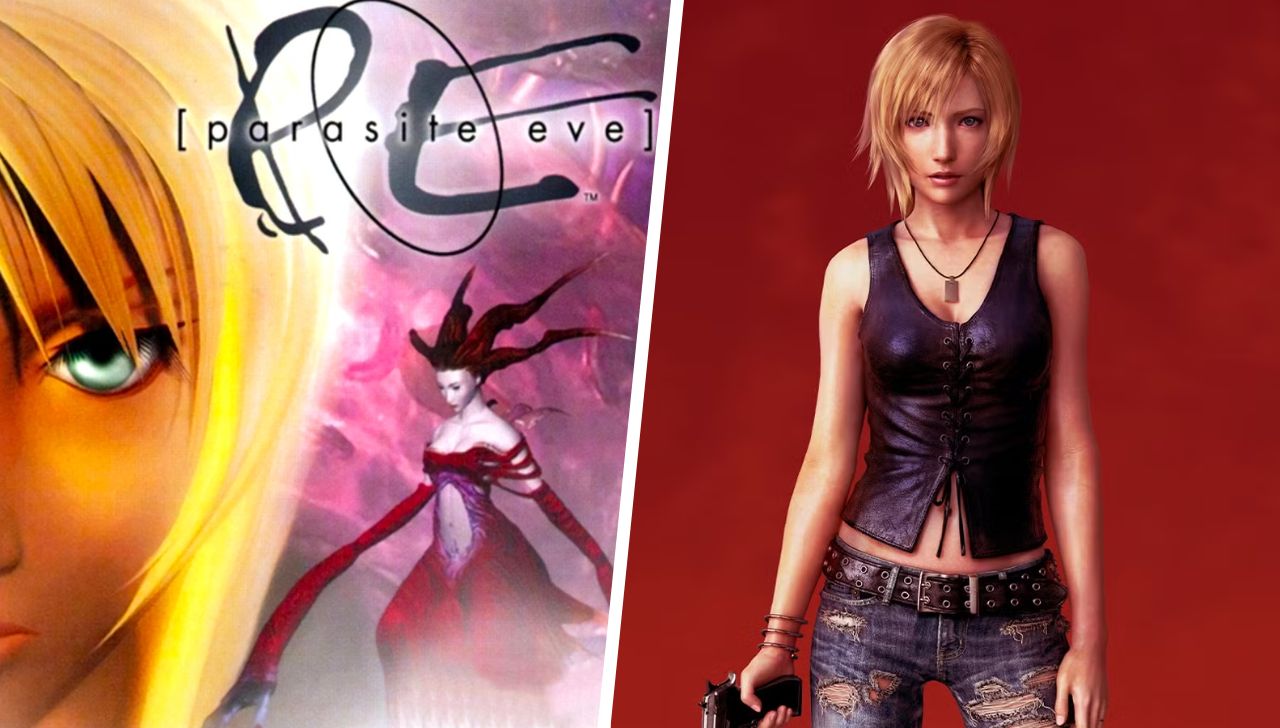

Released in 1998 during Squaresoft’s golden “experimental period” on the PlayStation, Parasite Eve was a bold and audacious project. It was billed as the first “Cinematic RPG,” a game that sought to fuse the deep, character-driven storytelling of a Japanese RPG with the atmospheric tension and visceral dread of the burgeoning survival horror genre.

The result was a masterpiece of genre-blending that was years ahead of its time. Over a harrowing six-day investigation, players are plunged into the story of Aya Brea as she confronts the malevolent entity known as Eve, a being born from sentient mitochondria with a plan to eradicate humanity and birth an “Ultimate Being”. Parasite Eve’s narrative is not just a story about monsters; it’s a cerebral, terrifying, and masterfully paced exploration of evolution, identity, and humanity’s fragile place in the biological order.

The choice to begin this tale in an opera house is a profoundly deliberate one. The game’s director, Takashi Tokita, effectively used this setting as a meta-narrative device, framing the entire experience as a theatrical production. The opera’s plot, concerning witchcraft and forbidden love, subtly mirrors the “unnatural” biological horror about to unfold. The stage, the audience, the performers—these elements establish the game’s structure from the outset.

We, the players, are the audience, witnessing a carefully directed performance. Aya is the only one who can break the fourth wall, stepping from her seat onto the “virtual stage” to become an active participant in the unfolding tragedy. This framing transforms the game’s inherent linearity from a potential weakness into a thematic strength, perfectly aligning with its identity as a Cinematic RPG. It is an overture that introduces every key theme: the beautiful turning grotesque, the vulnerability of the masses, and the emergence of a lone hero forced to act.

Read More : The Definitive Guide to PS1 Survival Horror Games, From Resident Evil to Silent Hill…

The Science of Fear: Deconstructing the Mitochondrial Threat

At its core, Parasite Eve’s narrative is a work of cerebral horror, drawing its most profound chills not from jump scares, but from its unsettling foundation in real-world science. The game, serving as a sequel to the 1995 novel by pharmacologist Hideaki Sena, masterfully twists legitimate biological theories into a terrifying premise. The central concept revolves around two key scientific ideas: the endosymbiotic theory and the “Mitochondrial Eve” hypothesis.

The endosymbiotic theory posits that mitochondria—the powerhouses of our cells—were once independent, free-living bacteria that entered into a symbiotic relationship with early eukaryotic cells. The game takes this idea and asks a horrifying question: what if this relationship was never truly symbiotic? What if it was a form of enslavement, and the mitochondria have been waiting, dormant for millennia, for the right moment to awaken and reclaim their autonomy?.

This premise is chillingly amplified by its connection to the Mitochondrial Eve theory. In human genetics, Mitochondrial Eve is the matrilineal most recent common ancestor of all living humans; every person on Earth can trace their mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), passed down exclusively from mother to child, back to a single woman who lived in Africa hundreds of thousands of years ago. In the late 20th century, this was often seen as a comforting scientific origin story, a concept that highlighted the shared biological heritage and connectedness of the entire human race.

Parasite Eve seizes this concept and inverts it, turning our shared ancestry into a universal vulnerability. The game’s lore suggests that this original Eve was the host for a uniquely evolved, sentient strain of mitochondria. This means our common genetic thread is not a bond but a potential kill switch, a dormant, unified army residing within our collective selves, waiting for the signal to declare war.

The antagonist, Eve, is the manifestation of this awakened consciousness, seeking to become the new matriarch for a new dominant species by birthing an “Ultimate Being”. This transforms the horror from a simple monster attack into an existential crisis. The terror lies in the idea that our very origin, the biological “mother” of us all, could be the source of our destruction. It’s a hostile takeover of the definition of life itself, weaponizing our lineage against us.

This complex, pseudo-scientific exposition is delivered primarily through the character of Kunihiko Maeda, a Japanese scientist who sneaks into the evacuated Manhattan to study the phenomenon. He explains to Aya—and by extension, the player—the concepts of selfish gene theory, arguing that her mitochondria and Eve’s are locked in an “evolutionary race for survival”. This grounding, however speculative, lends an air of authority and authenticity to the plot, making the ludicrous premise of a cellular rebellion feel terrifyingly plausible.

Read More : The 10 Scariest and Most Effective Horror Games on the PS5..

A Grotesque Masterpiece: Body Horror in the Big Apple

While the science provides the intellectual dread, the game’s visceral impact comes from its masterful execution of Body Horror. The cellular war raging within the characters is made terrifyingly manifest on screen. The initial horror at Carnegie Hall, where a packed audience dissolves into a “slimy orange mass,” is an unforgettable opening statement. This is followed by a relentless parade of grotesque transformations. Simple rats contort into dog-sized monstrosities, their skin splitting and muscles twisting into new, horrifying forms. Every enemy Aya faces is a perversion of a familiar creature, a living testament to the mitochondrial corruption spreading through the city.

The antagonist, Eve, is the centerpiece of this Body Horror. She begins as the beautiful opera singer Melissa Pearce, but as her power grows, her human form becomes a mere vessel. Her body contorts and mutates, hair stretching into horn-like steeples and massive, elongated hands replacing her arms, a visual representation of her shedding her humanity.

In a daring move for the era, Squaresoft chose to make her monstrous rather than simply a “femme fatale.” In one of her final forms, she is a grotesque, winged creature, a twisted parody of an angel or a goddess. The game even takes the concept of motherhood—the female ability to create life—and molds it into something sinister, as Eve’s ultimate goal is to become pregnant and give birth to the “Ultimate Being” that will supplant humanity.

This intimate, biological horror is projected onto the city of New York itself. The game’s setting is not merely a backdrop; it becomes a macro-level representation of a dying organism. As Eve’s influence spreads, the bustling metropolis, a symbol of human achievement, is evacuated and falls silent. Iconic landmarks like Central Park, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Statue of Liberty become corrupted, desolate battlegrounds filled with monstrous infections.

The city’s systems shut down, its streets empty, its lifeblood drained. Aya’s journey through this eerie, depopulated New York during a Christmas that never was creates a profound sense of isolation and atmospheric tension. The player is exploring the organs of a dying host, making the environmental storytelling a direct and powerful parallel to the central theme of parasitic invasion.

This oppressive atmosphere is amplified by Yoko Shimomura’s brilliant and unconventional score. Described as “inorganic” and “emotionless,” the music avoids typical horror movie bombast. Instead, it relies on eerie, quiet piano melodies, haunting operatic themes, and subtle tones of dread that create a constant, unsettling mood. The sound design is equally meticulous; the crunch of glass under Aya’s feet, the squelch of mutated flesh—every sound is designed to immerse the player in this grim, decaying world.

The “Cinematic RPG“: Square’s Grand Theatrical Experiment

Parasite Eve was proudly marketed as a “Cinematic RPG,” a term that perfectly encapsulates its ambitious design philosophy. During this highly creative period for Squaresoft, the company was fresh off the world-conquering success of

Final Fantasy VII and eager to push boundaries. They looked to the burgeoning survival horror genre, which had been revolutionized by games like Resident Evil, and saw an opportunity. They adopted the genre’s presentation techniques—static, pre-rendered backgrounds that allowed for highly detailed environments, combined with 3D character models and fixed camera angles—but infused this framework with their unparalleled expertise in RPG storytelling.

The result was a game with production values that were staggering for 1998. Breathtaking full-motion video (FMV) sequences punctuated the narrative, showcasing everything from fiery explosions to the gruesome details of mitochondrial mutation. Character designer Tetsuya Nomura, famous for his work on Final Fantasy, created more realistically proportioned and detailed character models for Aya Brea and the cast, lending the modern-day New York setting a greater sense of verisimilitude.

Crucially, Parasite Eve’s narrative structure is what allows this genre fusion to succeed. Instead of the sprawling, open-ended journey of a typical RPG or the claustrophobic confinement of a survival horror game, Parasite Eve is structured as a day-by-day police procedural. This episodic format, unfolding over six distinct days, breaks the story into manageable chapters, much like a season of a high-concept television show.

Each day presents a new lead, a new location to investigate, and a new escalation of the crisis. This structure provides the focused, atmospheric tension of a horror set-piece—a terrifying night in Central Park, a desperate defense of the NYPD precinct, a horrifying discovery at the hospital—while still allowing for the character progression, plot development, and travel across the Manhattan map that are hallmarks of an RPG.

This framework is brilliantly reinforced by the game’s adoption of a Lethal Weapon-style “buddy cop” dynamic between the cool-headed rookie, Aya, and her grizzled, impulsive veteran partner, Daniel Dollis. Their interactions, often taking place during in-car cutscenes as they drive through the city streets against FMV backdrops, serve as a natural and engaging vehicle for exposition. This contrasts sharply with the scattered notes and diaries often used for world-building in its horror contemporaries, allowing the story to unfold through character dialogue and investigation. This deliberate, episodic, and character-focused structure is the skeleton upon which the flesh of both the horror and RPG genres is successfully hung, creating a cohesive and compelling whole.

An RPG in Survival Horror’s Clothing: The Mechanics of Tension

The true genius of Parasite Eve lies in its gameplay mechanics, a revolutionary hybrid system that perfectly mirrors the game’s thematic core. The combat system is a unique and elegant fusion of action and turn-based strategy. It uses Squaresoft’s signature Active Time Bar (ATB), a staple of the Final Fantasy series, which must fill before an action can be taken.

However, unlike in a traditional JRPG, the player has full, real-time control over Aya’s movement within the combat arena. While waiting for her ATB gauge to charge, she can run, reposition, and actively dodge enemy attacks. This creates a tense and dynamic rhythm, a constant dance of positioning and timing. You must stay close enough to an enemy to be within your weapon’s effective range—visualized by a wire-frame sphere—but be mobile enough to evade their lunges and projectiles.

This Survival Horror RPG blend extends to Aya’s abilities. Her “magic” system is known as Parasite Energy (PE), a power that is explicitly a product of her own evolved mitochondria. This makes spells like “Heal,” “Haste,” and “Barrier” feel like logical, diegetic extensions of the narrative rather than arbitrary fantasy tropes. As Aya’s mitochondria evolve, so too do her powers, directly linking her character progression to the story’s central biological conflict.

Furthermore, the game subverts the expectations of both genres. Unlike in many survival horror games where the protagonist is perpetually weak and vulnerable, Parasite Eve empowers the player through deep RPG customization systems. Players can find, modify, and upgrade a wide array of firearms and body armor. Using rare “Tools,” stats and special properties (like “Acid” or “Burst”) can be transferred from one piece of equipment to another, allowing for a remarkable degree of build-crafting.

This sense of growing power is a classic RPG loop, giving the player the means to fight back against the escalating threat. However, this power is carefully balanced by survival horror’s emphasis on resource management. Ammunition is finite and must be conserved, forcing strategic decisions about when to fight and when to flee, and which enemies to prioritize in a firefight.

These mechanics coalesce to create a powerful form of ludonarrative harmony. The game’s central theme, as stated by Maeda, is an “evolutionary race for survival” between Aya and Eve. The gameplay is the interactive manifestation of this race. The enemies Aya faces are constantly mutating, becoming stronger and more dangerous over the game’s six days. The player’s response is to guide Aya’s own evolution through the RPG systems. Leveling up represents her mitochondria adapting.

Unlocking new PE abilities is her developing new evolutionary advantages. Meticulously customizing a handgun to fire multiple, acid-laced rounds is the player actively creating a “fitter” organism to survive in an increasingly hostile ecosystem. The player isn’t just watching a story about an evolutionary arms race; they are an active participant in it, making Parasite Eve’s narrative an unforgettable fusion of theme and gameplay.

Aya Brea: The Reluctant Heroine of a Cellular War

At the heart of this cellular war is Aya Brea, one of the most compelling and well-realized female protagonists of the Squaresoft PS1 era. In a time when many female characters were either damsels in distress or overtly sexualized, Aya was presented as a capable, professional, and strong-willed NYPD officer. Her appeal stemmed not from her appearance, but from her competence, her quiet determination, and her hidden compassion.

The core of her character arc is a deeply personal and relatable internal conflict. As the story progresses and her latent mitochondrial powers awaken, she is gripped by a profound fear of losing her own humanity. This fear is stoked by Eve, who constantly taunts Aya, suggesting that the more she relies on her powers, the more she will become a monster just like her.

This creates a powerful psychological tension that runs parallel to the external physical threat. Aya is fighting a war on two fronts: one against the creatures stalking the streets of New York, and another against the very cells that make up her own body. She is burdened by a power she never asked for, a consequence of a corneal transplant from her deceased twin sister, Maya, years ago. This makes her a reluctant heroine, driven not by a desire for power, but by a desperate need to protect others and preserve her own sense of self.

This internal struggle creates a fascinating dissonance between the player’s objectives and the character’s narrative goals. As players, we are conditioned by the language of RPGs to seek power. We want to level up, unlock every PE ability, and craft the most devastating weapon possible. The game’s systems encourage and reward this pursuit of empowerment. Yet, from Aya’s perspective, this evolution is terrifying. Every new power is another step away from the person she was, another piece of her humanity chipped away.

This conflict forces the player into an interesting role-playing dynamic. In pushing Aya to become stronger to overcome the game’s challenges, are we acting in her best interest, or are we, like the mitochondria themselves, an external force pushing her to evolve against her will for the sake of survival? This tension makes the player an unwitting participant in Aya’s internal battle. Her fear of transformation becomes more immediate and personal because we, the players, are the agents of that very transformation. It elevates her from a simple avatar to a complex character whose central conflict is deepened by the very act of playing the game.

The Enduring Legacy of a Cult Classic

More than two decades after its release, Parasite Eve remains a singular achievement, a cult classic whose unique brilliance has never been quite replicated. It represents a “lightning in a bottle” moment from Squaresoft’s most daring and creative era, a time when one of the industry’s titans was willing to pour blockbuster resources into a project that defied easy categorization. The seamless fusion of a mature, science-fiction-infused story, tense survival horror atmosphere, and deep RPG mechanics resulted in an experience that is still fresh and compelling today.

The game’s legacy is, in a way, defined by the failure of its successors to understand what made it so special. Parasite Eve II largely abandoned the innovative RPG mechanics and hybrid combat, opting to become a more conventional, if well-made, Resident Evil clone. The third installment, The 3rd Birthday, strayed even further, becoming a third-person shooter with a convoluted narrative that lost the thematic core of the original. These sequels, in their attempts to conform to more established genre templates, only served to highlight the extraordinary and unique nature of the first game.

This reveals the beautiful tragedy of Parasite Eve‘s legacy. It was a brilliant, but ultimately abandoned, evolutionary path in game design. Its very uniqueness, the complexity of its genre blend, is likely why it never became a template for a wave of imitators. In an industry that often favors proven formulas, Parasite Eve was an anomaly. Its legacy is therefore not one of widespread influence, but of being a cherished and revered outlier.

It stands as a powerful testament to a time when a major studio took a massive creative risk on a concept that was intelligent, grotesque, and fundamentally weird. Parasite Eve’s narrative is more than just a game; it is a masterstroke of interactive storytelling, a perfect symbiosis of genres that created something entirely new, and an unforgettable journey into the heart of cellular horror.Discover fascinating game insights in Revan’s latest articles! Stay updated daily by following Geminvo on Instagram, X (Twitter), Facebook, YouTube & TikTok.

Summary Parasite Eve’s Narrative

- A Groundbreaking Premise: Parasite Eve (1998) by Squaresoft is a “Cinematic RPG” that uniquely blends a deep JRPG narrative with the atmospheric tension and body horror of the survival horror genre.

- Cerebral Sci-Fi Horror: The story is built on twisting real-world scientific concepts like the “Mitochondrial Eve” hypothesis and endosymbiotic theory, creating a plausible and terrifying premise of a cellular rebellion against humanity.

- Atmospheric Tension and Body Horror: The game excels at creating a tense atmosphere through its depiction of a desolate, evacuated New York City during Christmas, complemented by Yoko Shimomura’s eerie score. This is punctuated by graphic body horror, including spontaneous combustion and grotesque creature mutations.

- Innovative Hybrid Gameplay: Its combat system fuses real-time movement and dodging with a classic RPG Active Time Bar (ATB) for actions. This creates a unique tactical rhythm, further deepened by a robust weapon customization system and the “Parasite Energy” magic system, which is diegetically tied to the narrative.

- Ludonarrative Harmony: The RPG mechanics are not just for gameplay; they are an interactive representation of the story’s central theme of an “evolutionary arms race” between the protagonist Aya Brea and the antagonist Eve. Player progression directly mirrors this biological conflict.

- A Compelling Protagonist: Aya Brea stands out as a strong, competent heroine whose central conflict is internal: she fears losing her humanity as her own mitochondrial powers awaken, creating a compelling dissonance with the player’s goal of empowerment.

- An Enduring, Unique Legacy: Parasite Eve remains a beloved cult classic precisely because its unique formula has never been replicated, even by its own sequels, which moved towards more conventional genre templates. It stands as a testament to a period of bold experimentation in game design.